Fine-tuning flock management to reduce dag

Edward Blackwell was one of the producer advocates and site hosts in the MLA-supported ‘Transitioning towards non-mulesed sheep’ PDS. Edward’s flock has been non-mulesed since 2017.

With nearly a decade of experience in running a non-mulesed flock, south-west Victorian Merino producer Edward Blackwell joined the MLA-funded ‘Transitioning Towards Non-Mulesed Sheep’ producer demonstration site (PDS) project not only as a producer advocate to support his peers who were just starting their journey to non-mulesed, but as an opportunity to fine-tune his flock management to reduce dag.

The Blackwells began their non-mulesing journey in 2007, when they participated in an Australian Wool Innovation breech clip trial as an alternative to mulesing. The following year, they ceased mulesing on a small group of lambs as a trial but continued to tail strip before ceasing mulesing on their entire 2009 drop.

However, Edward said it wasn’t until 2017 that they felt confident they could manage the welfare of the flock without the aid of tail stripping.

Making the decision to run a demonstration site

With a breeding objective that included lowering breech wrinkle, the Blackwells have been purchasing plain-bodied rams and classing out ewes with high dag and wrinkle to ensure they can keep their flock non-mulesed.

“With dag, crutching takes longer, adds to flystrike pressure and loss of wool value,” Edward said.

“We crutch our own sheep and readily identify ewes that are too wrinkly or flystruck, and we put them into a terminal mob along with any ‘daggy’ ewes.

“Even though we were a long way down the path of non-mulesed and thought we were pretty good at completing regular worm egg counts, dag was still an issue, and we felt that we weren’t being consistent enough with managing it,” he said.

“We considered worms, lack of fibre or other pasture factors being the cause of dag but we weren’t sure where to begin with our investigations.

“So, we decided to join the ‘Transitioning Towards Non-Mulesed Sheep’ PDS as an opportunity to investigate the impact of worms on dag in our weaners, and fine tune our flock management.”

On-farm changes

The Blackwells hosted a demonstration site that aimed to investigate factors which could be contributing to dag and the effectiveness of improved worm control during winter and early spring. The demonstration was relevant to both flocks which are no longer mulesed and those still being mulesed (which have a high incidence of dag during the winter and spring, particularly in weaners).

In June 2022, 630 ewe weaners from the Blackwells’ 2021 drop of lambs were randomly drafted into three treatment groups.

They were shorn, so they entered the trial dag-free. At the start of the trial, the weaners were all weighed and their worm egg count (WEC) determined. Their electronic identification (eID) was used to identify and track their progress.

Commencing application on 23 June 2022, the treatment groups focused on comparing the effectiveness of:

- the normal practice short-acting drench

- a long-acting injection drench with an oral primer drench

- a short-acting drench with a mineral supplement injection.

“The long-acting drench was used with the aim of possibly ruling out worms as a contributing factor for dag, leaving bacterial infections as a potential cause of dag to investigate,” Edward said.

The Blackwells ran the sheep as one mob and continued their standard practices of rotational grazing and providing fibre (hay) in the paddocks during winter.

After drench treatments were applied, the Blackwells tracked the progress of each treatment option by recording their WECs and weights every 30 days.

Results

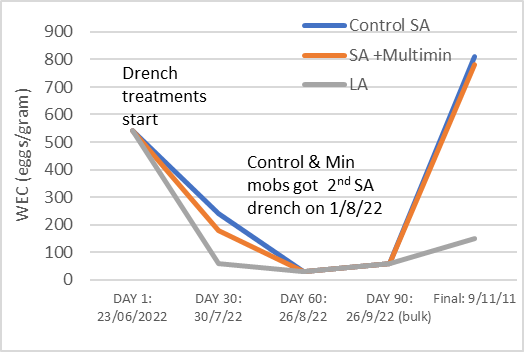

During the trial, the decision was made based on the day 30 WEC results to drench both short-acting treatment groups a second time on 1 August (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Worm egg counts

*Note that the day 90 worm egg count (WEC) results reflect the entire mob as opposed to individual treatment groups

“By the end of the trial (early November), the WECs for the two short-acting treatment mobs were substantially higher than they were for the long-acting treatment mob,” Edward said.

“This indicated these mobs may have required a third drench at day 90 to keep their WEC in check.

“Overall, it was quite clear that the long-acting treatment was successful in reducing worms and allowing for a higher daily weight gain and a lower average dag score.

“We also saw an improved annual net benefit of $5.18/head within the long-acting treatment group.”

|

Treatment |

Weight gain (kg) 23/6/22 to 9/11/22 |

Dag score 9/11/22 |

|

Control (short-acting Triple drench) |

15.6 |

2.6 |

|

SA + Mineral injection (short-acting Triple drench + Min) |

15.3 |

2.3 |

|

Long-Acting (LA moxidectin + Zolvix) |

17.2 |

1.8 |

Figure 2: Weaner weight gains and dag scores

Importance of regular WEC monitoring

Edward said the results highlighted two opportunities to fine-tune dag management in his flock.

“The PDS methodology we used with the three trial groups meant we could identify that the main cause of dag that year was, in fact, worms,” he said.

“It also highlighted the importance of monitoring WECs every 30 days during winter to early spring – something we didn’t realise we were a bit behind the eight-ball on.

"We had been monitoring WECs every 5–6 weeks, but we really needed to be doing them every four weeks.

“This can make a big difference in the middle of August as weaners can quickly pick up worms and dag can accumulate.”

Following their involvement in the PDS, the Blackwells made the decision to stick with short-acting drenches – particularly for their weaners and hoggets – as they didn’t want to risk drench resistance occurring from the blanket use of long-acting drench.

“Running weaners and hoggets into the yards to drench in necessary is something I’m confident we can do at any time, and that more frequent monitoring of WEC will enable us to be timelier with that decision making.”