COVID-19 putting US beef supply chains to the test

COVID-19 has created a dichotomy for the US meat industry. Never before has so much meat been purchased through retail channels in such a short period of time, nor modern supply chains put to the test in order to meet that demand.

The US is both a major buyer and competitor of Australian beef. So, how is the disruption from COVID-19 throughout the US supply chain impacting Australian exports?

The run on retail

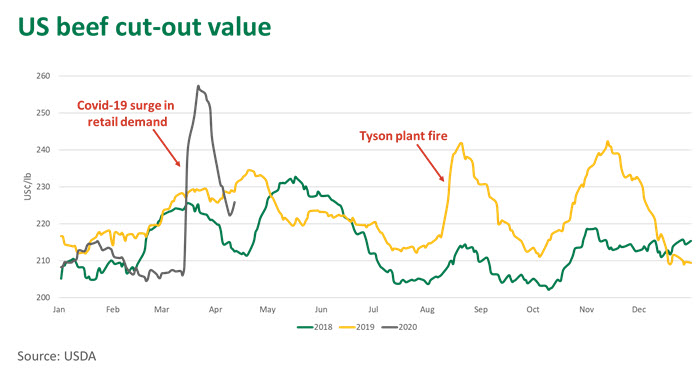

The last month has been a roller-coaster for the US wholesale beef market. On Friday 13 March, the US choice cut-out value (a price indicator of the aggregate value of carcase primals) was 208US¢/lb and the country had just 2,100 confirmed cases of COVID-19. By 20 March, COVID-19 cases had climbed to 19,400 and the cut-out had notched its largest ever weekly rally, to finish at 254US¢/lb.

Panic buying – as fear of impending regional shutdowns, movement restrictions and food shortages set in – and retailers scrambling to keep shelves stocked triggered the incredible run on wholesale beef prices. Beef primals that go into mince, such as rounds and chucks, recorded particularly strong gains. Loins cuts, typically destined for foodservice channels, picked up little support during the rush.

As freezers have filled and retail shelves have been restocked, the panic buying has subsided and almost as quickly as the wholesale market went up, it has come back. At the close of Tuesday 14 April, the US beef cut-out value was back to 227US¢/lb. Moreover, foodservice cuts have come under even greater pressure, with wholesale ribset, loin and brisket prices back 29%, 23% and 28% year-on-year, respectively. Meanwhile, chucks and rounds, geared to retail channels, are up an impressive 26% and 49% year-on-year, respectively.

While support for secondary cuts is great for US packers, they still need to balance the entire carcase and make money off those traditionally higher-value foodservice items. The US summer, and the potential for increased home-grilling demand, can’t come soon enough.

Australian beef exports

For Australian beef exporters, the rush on product last month came and went too quickly to support trade volumes – Australian beef shipments to the US were back 30% year-on-year in March.

While Australia does send a lot of manufacturing beef to the US, this product typically goes into frozen burger patties for the vast array of fast food chains across the country. Most retail mince is fresh domestic beef. While some fast food chains have successfully adapted to take-away and home delivery models, a recent Datassential survey indicated quick service retail sales were back 42% in late-March since the start of the outbreak. Last week McDonald’s announced that US sales declined 13.4% in March.

Processors facing slowdowns, closures

US packers ramped up weekly kills in response to the retail demand spike in late March. However, those increases have quickly reversed as plants have slowed chains to implement employee distancing measures and increase sanitation interventions. For instance, the Cargill beef plant in Fort Morgan, Colorado has had positive cases of COVID-19 amongst staff and announced ramped up precautionary measures this week.

Moreover, some plants have been forced to close doors in response to outbreaks amongst staff members. Notably, a JBS beef plant in Greeley, Colorado and a Smithfield pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota have both announced temporary closures this week. Other slaughter and further processing plants have also reported reduced capacity or temporary shutdowns.

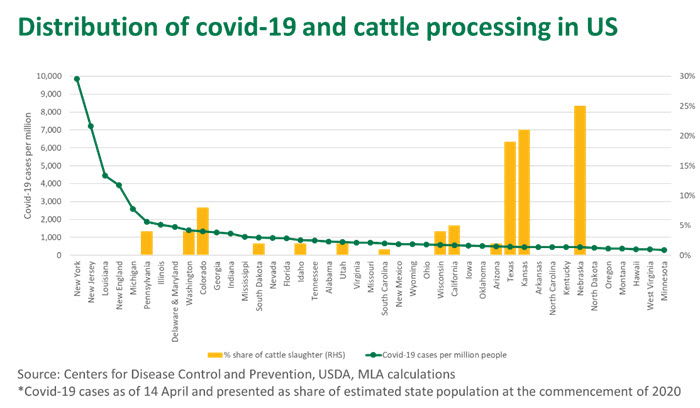

As the number of COVID-19 cases in the US increases, additional plants may be forced to take greater precautions, slowing processing chains further, or temporarily close. Managing workforces will become increasingly challenging. However, comparing the density of COVID-19 cases and the distribution of US cattle slaughter highlights, generally, key cattle processing states have so far been less affected by the virus.

Reflecting disruption at the JBS Greeley and Cargill Fort Morgan plants, Colorado is one of the few major cattle processing states (accounting for 8% of national slaughter in 2019) with a relatively high incidence of COVID-19. The big cattle states of Nebraska, Kansas and Texas, which accounted for almost two-thirds of national slaughter last year, all had fewer than 500 cases per million people as of Tuesday. For context, Queensland and Victoria had just over 200 cases per million on Tuesday, while NSW had 376.

That said, even if a small portion of processing capacity is taken out of the system, this can still place significant pressure on pricing, as seen by the Tyson plant fire in Garden City, Kansas last August. That plant was estimated to account for 6% of national fed cattle slaughter and, compounded by the alignment with Labor Day long weekend demand, triggered a 12% spike in the cut-out value over the eleven days post-fire. Prices subsequently calmed as processing capacity shifted to other plants and supply chains adjusted.

Steiner Consulting estimate fed cattle slaughter in the US last week was back 23% on where it peaked two weeks prior and was 18% below year-ago levels. Such a drastic supply squeeze could again pressure wholesale meat prices and, if plants can’t build up capacity, markets may remain elevated. However, even an ongoing slowdown in US cattle slaughter will pose limited opportunity for Australian beef to fill a gap. Australia exports predominantly grassfed manufacturing beef and chilled grassfed primals which target specific channels in the US – not the cornfed beef the majority of US retail is geared to.

Moreover, a sustained substantial slowdown in US processing seems unlikely given there are still very large numbers of market-ready cattle coming through the system. Cattle won’t stop growing regardless of how disruptive COVID-19 is and they will still need to be processed. US fed cattle prices declined 5% last week and are 16% below year-ago levels. If that trend continues, US packers will have greater incentive to find workarounds to managing labour forces.

Concern for ports

The US meat industry is domestically oriented, with most product transported internally via a substantial rail and road network. However, for product that is imported or exported, seaports present a major bottleneck in the supply chain.

Significant disruption was witnessed in Chinese ports, particularly Shanghai and Tianjin, during the COVID-19 outbreak through February, when port clearances ground to a halt due to mass labour shortages. The backlog of reefer containers in China have only returned to global circulation in recent weeks.

Like China, the US is at risk of virus outbreaks amongst employees in ports and supporting logistics networks curbing the movement of product. In addition, the slowdown in US consumer spending, especially on non-essential items, has seen many retailers and distributers delay the receival of imported products, compounding the build-up of containerised freight sitting in US ports. As consumer demand pull-through remains weak and containers accumulate, the downside risk from a COVID-19 outbreak amongst port employees will increase.

A slowdown in US ports and their ability to process reefer containers could be positive or negative for parts of the Australian beef industry, depending on the port impacted. However, it will likely be a net-negative and, at a minimum, reduce the availability of reefer containers in circulation and push up freight rates.

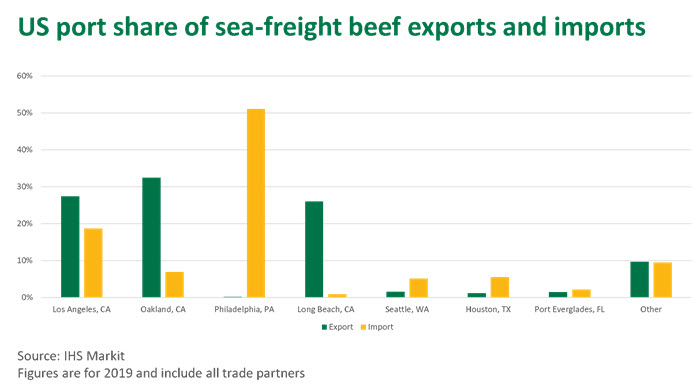

Philadelphia accounted for almost 60% of all inbound Australian beef into the US last year, with much of the remainder entering via California, particularly Los Angeles and Oakland. While California is a closer trans-Pacific route from Australia, much enters the US North East due to proximity to cold stores, grinders and a large consumer base. Philadelphia also processed 59% of all inbound Australian sheepmeat last year.

Given Philadelphia sits within Pennsylvania, which has the fifth greatest number of COVID-19 cases and borders other states with high incidences of the virus, there is risk of the port being impacted by labour shortages or downstream logistics disruption.

Due to proximity to North Asian markets, most US beef exports are shipped out of California. In fact, Oakland, Los Angeles and Long Beach accounted for 96% (or 640,000 tonnes swt) of US beef exports to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and China in 2019. While the incidence of COVID-19 per million people remains lower in California, an outbreak and slowdown in any of these critical ports could impact US beef exports into North Asia. USDA weekly reports indicate US beef export continue to flow freely, but Australian grainfed beef would be the primary beneficiary if an extended slowdown in US shipments, to the likes of Japan and Korea, were to occur.

COVID-19 is impacting various facets of the US beef supply chain. Short term opportunities for increased Australian volumes into the US domestic market appear limited, especially given the Australian beef supply outlook for the year ahead is tight. Moreover, US consumer demand remains weak, with 15 million Americans filing for unemployment benefits over the last three weeks and uncertainty as to when economy will be able to open back up. However, if US processing is hit further or California ports are substantially disrupted, Australian beef may be temporarily shielded from US competition elsewhere, particularly in North Asia.

© Meat & Livestock Australia Limited, 2020